Mesh Networks for Cellphone Users

Mesh networking—applied to internet connections—is the concept of connecting devices to the internet throughout one another instead of directly relying on cellphone cells or any other ISP (Internet Service Provider) proprietary infrastructure. The adoption of this has profound implications for all humans and the future of civilization. What follows is an analysis on how they could be adopted and what implications go along with their adoption.

To start this, let's make sure you understand how a mesh network works and to do so consider the following example. Everyone's been in a crowded place—let's say a concert—and had the misfortune of getting extremely slow internet signal. In today's world this happens because of the limited amount of cellphone cells that surround any given location and their limited bandwidth and processing power. Now, imagine that instead of connecting to a single cell you could easily connect to a neighboring device that would then connect to another device until some master device—the one that's nearest to an actual internet access point—lays off all the messages into the interconnected network1. This same process is inversely repeated when you're trying to receive a message and your device is found thanks to the use of networking protocols2.

From this line of thought some issues start coming up. First, how are you sure the traffic that gets relayed unto someone else's phone remains secure and your privacy is maintained? This issue is where the protocols mentioned earlier become relevant, as any piece of technology they are error and hacker prone, but all-in-all they're extremely resilient tools. Second, why any single user would be willing to give personal resources to some else? This problem has no clear answer, but to try and sort things out let's consider some anthropological arguments and the basis of human psychology.

To start things off in the quest to answer the second dilemma let's look at how civilization reacts to new technologies and how it adapts to its surroundings. The adoption of any new technology depends, arguably, in two things: somethings popularity—this could be a product or a service—and its added value based on the existing competition. The prior trend becomes clear when we consider the development of keyboards, the layout we use today—QWERTY—is a result of its popularity and not its efficiency3. Nonetheless, keyboards—and basically any other thing in this situation—are likely to change in the coming years towards something with greater efficiency—say a new layout or the evolution to more novel ways of interacting with technology, this could be brain to computer interfaces. The type of change that something like mesh networking would bring to the world would be based on this latter adoption tendency—its added value—so the average consumer, in the end, will have little to do with the decision.

To go along with this argument there is some common ground that needs to be held:

- Most people see technology as a black box with no clue as to how it all works.

- The approval of a large group of people validates something—this could be a product or a service—to most individuals.

- If this thing—whatever is being implemented—continues to work with no negative impact to the consumer, they will have no problem with the update and most people won't even notice the change.

Considering these the following formulation fits in seamlessly: the mass adoption of mesh networking between cellphone users depends on it working in a more efficient way with no negative effect on the consumers. Let's remember that people see this as a black box so public debate doesn't really help; expert panels and regulatory agencies must do the heavy lifting4.

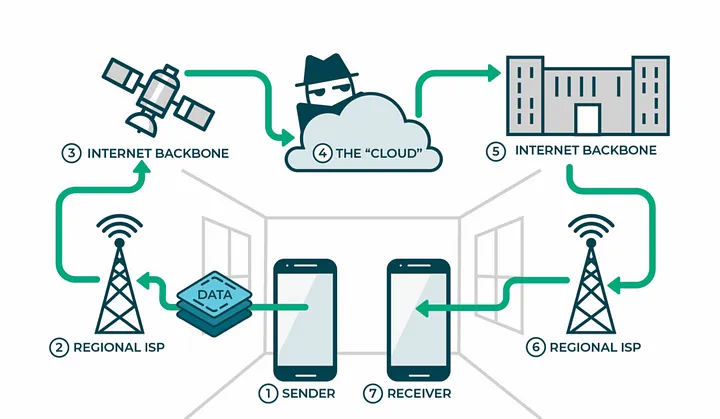

Getting back on the technical details of these networks let's consider how a WhatsApp message is currently sent to a person standing next to you and how mesh networks become relevant. In the network's current form, the message would travel from your phone to and internet access point where it would be passed on to the internet's backbone—fiber optic cables, switches, routers, among other components. Once all this is done the message arrives to a WhatsApp server—the "cloud"—and from there the previous process is inversely done until it reaches the person sitting next to you. The following image from McLennan (2019) shows how the message is sent, there are some clear inefficiencies in this model.

Using mesh networking in this interaction would make things a lot easier, instead of relying in so many nodes, information would be directly transmitted from one device to another. This would also enable communication between devices even when there's no internet access point nearby. Implementing this technology would require the application to work with mesh networks, but that's not a mayor problem, implementing these platforms is not hard and some have already been created5. Imagine how cool it would be if a message to a friend that you've lost inside a mall where you have no WiFi would simply travel between other people's phones6 until it reached your friend's; this cuts off a lot of costly and unnecessary intermediaries.

The scope of this writing has been met with these few lines, but more information on this topic can be found in the bibliography. I hope you liked this brief introduction to mesh networks, their implications, and where they're currently standing. To leave you with some final words about the topic and my opinion upon this I leave the following paragraph.

As the world continues to adopt new technologies and the IoT revolution continues to accelerate there will be more connected devices than ever before. This will add nodes to mesh networks and thus make them more robust, not using this infrastructure to advance our current issues would be unthinkable. From here—I would like to think—the use and validity of mobile mesh networks becomes a matter of when, not a matter of why. The benefits that come from using them are immense and the cost is low, as a software you don't have to recreate this from scarce materials, you simply add a few lines of code and libraries to an existing device or application and voilà, you're in.

References:

- Bocetta, S. (1994) Why Mesh Networks Are the Future of Free Internet Access. April 6, 2022. FEE, website: https://fee.org/articles/why-mesh-networks-are-the-future-of-free-internet-access/

- Jones C. (2018) New ideas about new ideas: Paul Romer, Nobel laureate. October 25, 2021. Vox EU, website: https://voxeu.org/article/new-ideas-about-new-ideas-paul-romer-nobel-laureate

- McLennan A. (2019) What is Mobile Mesh Networking. April 25, 2022. Medium, website: https://medium.com/rightmesh/what-is-mobile-mesh-networking-964732814943

- Waldrop M. (2019) The Dream Machine (Fourth Edition). USA: Stripe Press.

- Wldrop M. (1992) Complexity – The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. USA: Stripe Press.

Footnotes

-

This is the actual name of the internet. In the old days the world had a lot of different networks—the most famous one is the Arpanet—and when the internet came along it based its infrastructure on the interconnection of all this networks, thus the name. ↩

-

For more on this lookup TCP/IP and UDP, this are the internet's main protocols. ↩

-

This is an economic effect called lock-in and was proposed by Kenneth Arrow, an economic wiz and Nobel Laurette. This was further studied by economist Bryan Arthur in his analysis of increasing returns in economics. ↩

-

Having an educated public would make this a lot easier, the population would not depend on centralized decisions and there would be a lot more information about this topic. Sadly, this is not our reality and there's no near-term scenario where this could happen. ↩

-

Check out this company that's already doing mesh networks for last mile implementations. ↩

-

The mesh networking protocol would encrypt your data and thus protect your privacy. Networks in their current form do the same thing, but the "jumps" generally happen within routers and switches. ↩